Digital space is making Nicholas Bourriaud’s relational aesthetics theory into garden variety. Art is becoming more profoundly shared and experienced due to the digital world.

Relational aesthetics is Bourriaud’s explanation of art practice that goes beyond the typical display of an art object within an art institution. This art “takes as its subject the entirety of life as it is lived, or the dynamic social environment” (Chayka. Hyperallgeric. 2011.) Relational art is Marina Abramovic inviting visitors to sit across from her (and watch people sit across from her) throughout the open daily hours at MoMA for half a month. It’s painted pianos sprawled across Atlanta in September for Pianos for Peace. It’s the pinkest pink that anyone but Anish Kapoor can purchase and use.

What is most peculiar about relational aesthetics is its self-awareness of choice. Artists create experiences for those to relate to variably depending on the social and cultural dynamic of the viewer. The inherent open-mindedness of relational art invites a wider audience into the den of contemporary art. It offers dinner and encourages a few extra minutes for dessert, only if you wish. However, those that keep to themselves do not often partake; relational art is a harder pill to swallow for those who would rather have space to observe a framed object.

While Pianos for Peace invites any passerby to take part in playing with Instagram ready pieces of art, there are still those who opt out of the experience.

Digital space offers a (more or less) private encounter.

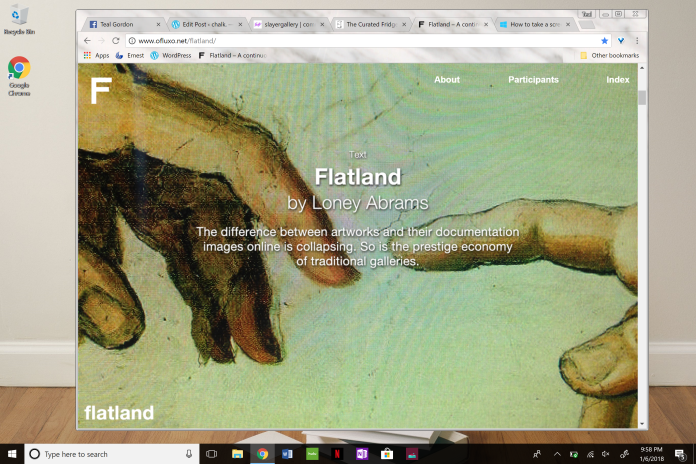

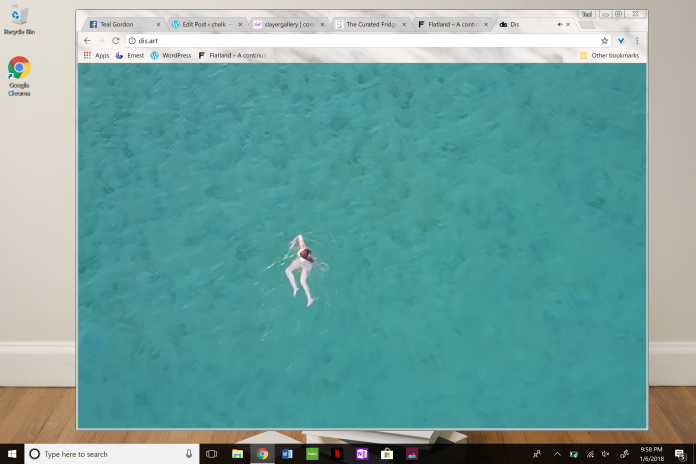

Digital spaces of experience such as Ofluxo.net’s Flatland, a continuous feed of art content or dis.art, an “edutainment” site created by a group of post-internet artists, have the privacy to experience contemporary art with introversion, but still under the umbrella of relational aesthetics.

Once you type in your e-mail (with little to no context of the results), Dis.art greets you with a purple-lashed eye encased in a yellow mouth saying “hello” in a pleasant tone. You’re then barraged with seemingly unrelated visuals streaming across the window: realistic scenes, digitally manipulated scenes, phone-footage, complete CGI characters, etc. If you feel claustrophobic, you’re able to click on the “DIS” logo, only to find a vague description of the project that informs you that videos will be available for 30 days.

Once you venture to your e-mail for hope of an explanation, you’re informed that dis.art isn’t yet live, but once it is its goal is “to inspire, inform, and mobilize a generation around the critical issues facing us today and in the future” by utilizing a video platform.

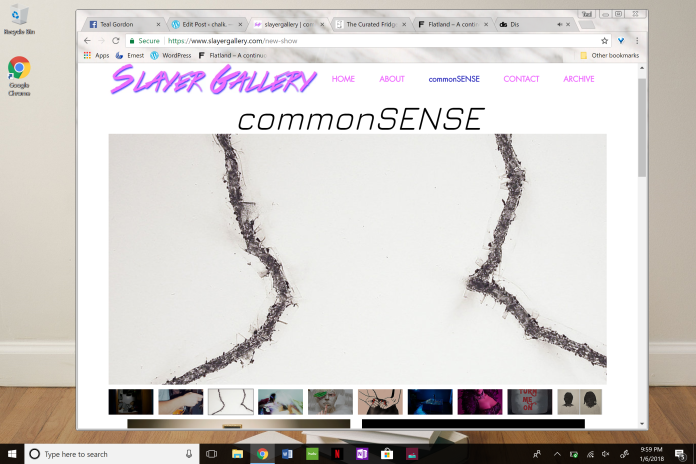

Other digital-only experiences include online art galleries like Slayer Gallery or real-object-experienced-online gallery called The Curated Fridge.

The digital realm opens relational aesthetics up via shifts in the accessibility and intrigue of contemporary art to an audience beyond MoMA, the pinkest pink, and Pianos for Peace; it ventures into the home, the mobile phone, the screen we easily relate with.